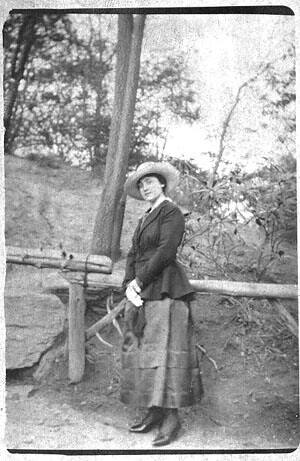

Gertrude D'Ippolito, c. 1920

Gertrude told stories about her parents, the D’Ippolitos, and her childhood.

Was it true that Gertrude wanted to be an opera singer but her father, Giuseppe D’Ippolito, called Don Peppino, wouldn’t let her? Yes. He was an old-world gentleman. He didn’t think such a career was dignified or proper for a young girl. At least that is how I first heard the story, but there is another version: Gertrude gave up singing lessons because of her fresh piano teacher...

Gertrude told stories about her parents, the D’Ippolitos, and her childhood.

Was it true that Gertrude wanted to be an opera singer but her father, Giuseppe D’Ippolito, called Don Peppino, wouldn’t let her? Yes. He was an old-world gentleman. He didn’t think such a career was dignified or proper for a young girl. At least that is how I first heard the story, but there is another version: Gertrude gave up singing lessons because of her fresh piano teacher...

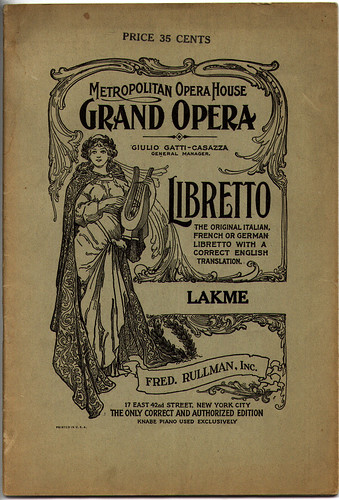

opera libretto

Aunt Paula, John Massimo’s and Joseph’s younger sister, heard another version: Gertrude took singing lessons. She was apparently so good and had such a range that at one of these lessons after hitting all the high notes, her teacher was overcome by her talent and grabbed her and kissed her on both cheeks and embraced her. She was horribly embarrassed and went home and told her parents. Don Peppino told her that she didn’t have to continue.

Perhaps that is what is the most fun about hearing all these stories. They tell moments in the lives of people you love from a time when you didn’t know them. Also fun is how these tales are told slightly differently each time. Or told differently by different people.

He returned to Palermo, to take a position as chef at the manor house of the local Duke. When the Duke and his family vacationed in England, they took Peppino with them. The ducal family wanted to keep him on in service, but Peppino wanted a better life (he was only living in a very small room in the back of the servant’s quarters), so he started saving money to go to America.

Aunt Paula, John Massimo’s and Joseph’s younger sister, heard another version: Gertrude took singing lessons. She was apparently so good and had such a range that at one of these lessons after hitting all the high notes, her teacher was overcome by her talent and grabbed her and kissed her on both cheeks and embraced her. She was horribly embarrassed and went home and told her parents. Don Peppino told her that she didn’t have to continue.

Perhaps that is what is the most fun about hearing all these stories. They tell moments in the lives of people you love from a time when you didn’t know them. Also fun is how these tales are told slightly differently each time. Or told differently by different people.

Maybe Gertrude lost her big opportunity to pursue a career in the opera, but she always loved music. I can remember hearing her sing along to the Metropolitan Opera on the radio on Saturdays. She instilled in me an appreciation for opera, especially Puccini. She loved the most dramatic stories, like La Forza del Destino and Tosca.

Neither Don Peppino nor his wife, Giovannina Quartuccio, spoke any English, only Sicilian. Don Peppino was born in Sicily. His mother’s name was Maria, but it is difficult to go back any earlier than that.

Neither Don Peppino nor his wife, Giovannina Quartuccio, spoke any English, only Sicilian. Don Peppino was born in Sicily. His mother’s name was Maria, but it is difficult to go back any earlier than that.

A story from Peppino's childhood: When he was an altar boy in Palermo, Sicily, he and his friend Giovanni decided to have some fun after the church service was over. As the procession of churchgoers made its way out of the church, the two lingered and crept downstairs below the altar to the catacombs beneath the church. They had a great time chasing each other through the tunnels, making echoes as they screamed at each other and the rats. But they eventually became bored and decided to head for home. They quickly realized that no matter where they walked, they never seemed to find the exit. Laughter soon changed to tears as it seemed to get darker and darker around them. Above ground, chatting and socializing with their neighbors, their families finally noticed the little boys absence and reentered the church to effect a rescue. They found the two little mischief-makers hugging each other, sobbing in the center of the catacombs.

When he was a teenager, Peppino left home and worked as an apprentice galley boy in the maritime service. This was his first professional experience with cooking. As a young man, he worked throughout Italy in all manner of restaurants, training and learning, until he finally became a chef.

He returned to Palermo, to take a position as chef at the manor house of the local Duke. When the Duke and his family vacationed in England, they took Peppino with them. The ducal family wanted to keep him on in service, but Peppino wanted a better life (he was only living in a very small room in the back of the servant’s quarters), so he started saving money to go to America.

una lettera

Giovanna Quartuccio was born in 1861 in Sicily (Palermo? Marsala?). According to Paula, Giovanna was a battered wife. Her husband, a stone mason, ______Cosentino, was mistreating her. Her mother, Filomena, from Piana dei Greci, and father, Giacomo Quartuccio, also a mason (and a card player and gambler) rescued her when they heard of her plight. A man from the town where Giovanna was living came to their town and and told them that they better come and look at their daughter. She was battered, six months pregnant at the time with Frank Cosentino, and almost unrecognizable. Her husband was away. Her parents told all of the neighbors that they were taking her home and they better never lay eyes on the husband again. Was she divorced? Annulled? A few years later she met Giuseppe D'Ippolito (Don Peppino).

There is another version that John Massimo heard that says that Peppino effected the rescue, and that his brothers cautioned him that it was a dangerous situation that could lead to trouble, but that Peppino didn’t care, he wanted her.

Don Peppino and Giovanna were married and they raised Frank Cosentino along with the rest of their children: Gaetana (Gertrude), Frank (they named their boy, Frank, too!), Mary, Filomena (Fanny), James and Albert.

Giovanna Quartuccio was born in 1861 in Sicily (Palermo? Marsala?). According to Paula, Giovanna was a battered wife. Her husband, a stone mason, ______Cosentino, was mistreating her. Her mother, Filomena, from Piana dei Greci, and father, Giacomo Quartuccio, also a mason (and a card player and gambler) rescued her when they heard of her plight. A man from the town where Giovanna was living came to their town and and told them that they better come and look at their daughter. She was battered, six months pregnant at the time with Frank Cosentino, and almost unrecognizable. Her husband was away. Her parents told all of the neighbors that they were taking her home and they better never lay eyes on the husband again. Was she divorced? Annulled? A few years later she met Giuseppe D'Ippolito (Don Peppino).

There is another version that John Massimo heard that says that Peppino effected the rescue, and that his brothers cautioned him that it was a dangerous situation that could lead to trouble, but that Peppino didn’t care, he wanted her.

Don Peppino and Giovanna were married and they raised Frank Cosentino along with the rest of their children: Gaetana (Gertrude), Frank (they named their boy, Frank, too!), Mary, Filomena (Fanny), James and Albert.

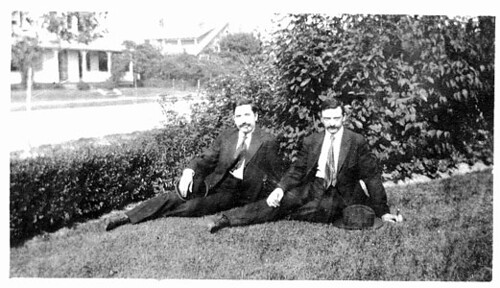

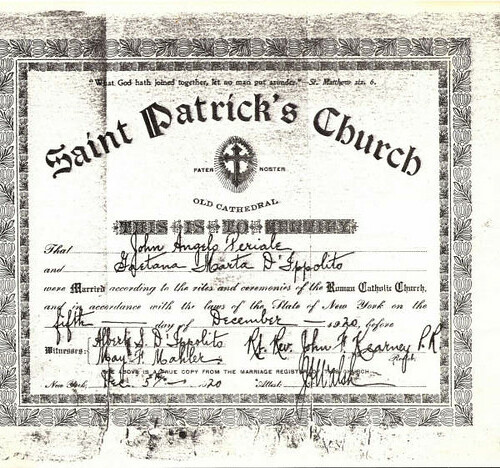

Frank D'Ippolito and Frank Cosentino (cutter, garment district, New York), c. 1920, probably Spring Lake or Belmar, N.J.

Don Peppino was able to bring Giovanna and their children to America with his savings. They settled in New York City where he worked as a chef at the Ritz Carlton, among other places. In 1910 he opened his own restaurant on Elizabeth Street and the family settled in to a nice life in America.

Don Peppino was able to bring Giovanna and their children to America with his savings. They settled in New York City where he worked as a chef at the Ritz Carlton, among other places. In 1910 he opened his own restaurant on Elizabeth Street and the family settled in to a nice life in America.

Gertrude loved to tell a story about her mother Giovanna’s grandfather, Francesco. When Giovanna’s father, Giacomo Quartuccio’s mother died, his father, Francesco, married again—a widow with 5 or 6 children. This was Francesco’s second marriage and he was only 16 or 17 years old. Francesco died soon after, leaving the widow with his money, his possessions—everything. The family was outraged, as it was believed that according to Sicilian law (hereditagium), the land and the house should have gone to Giacomo, the first-born son. Family legend claims that the widow stole everything while they were all at the funeral. She supposedly hid all of Francesco’s hard-earned money under her mattress. Supposedly some family members tried to reclaim this land (in Piana del Grecia?), but with no luck. Giacomo’s wife, Filomena, exacted revenge in her own manner. She would wait until harvest time and then go and take her pick of the harvest off of her deceased father-in-law’s land. If this story is accurate, the family held this grudge against the “evil widow” a long time—time enough for Giacomo to grow up and marry Filomena. Gertrude told another strange variation on this legend: the “evil widow” died in a fire and they found all the money under the bed burnt with her!

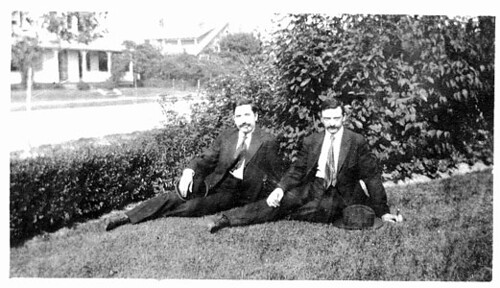

The family has always supported artistry.

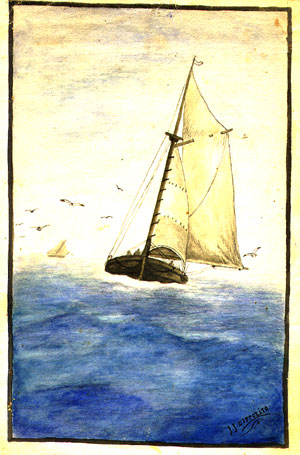

Gertrude’s brother James Gabriel was a painter. He had a headstrong and temperamental personality. He didn’t take very good care of himself and unfortunately died at 21, of pneumonia, in the 1918 flu epidemic, while attending St. Joseph’s College on Long Island. James loved poetry, Tennyson in particular, and was talented in sewing. He made his own suit. The D’Ippolitos also sent him to classes at Cooper Union. I have his only surviving artistic efforts, a watercolor, a gouache, and a large pastel.

Gouache by James Gabriel D'Ippolito, c. 1916.

Albert, a year older and more aggressive than his brother, finished college. It was expensive for Don Peppino to send the two boys to school on Long Island. There wasn’t enough money to also continue sending Gertrude to school at Old St. Patrick’s, so Gertrude couldn’t finish—she never graduated high school. This new-century yet still old-world family still valued a boy’s education over a girl’s.

Albert, a year older and more aggressive than his brother, finished college. It was expensive for Don Peppino to send the two boys to school on Long Island. There wasn’t enough money to also continue sending Gertrude to school at Old St. Patrick’s, so Gertrude couldn’t finish—she never graduated high school. This new-century yet still old-world family still valued a boy’s education over a girl’s.

With a chef for a father, Albert received amazing boxes of food sent from home. He became quite a hit at college, his classmates eagerly anticipating mailings filled with such Sicilian delicacies as caponata, an eggplant relish:

Don Peppino's Caponata

1 medium eggplant

1 cup black olives

5 onions

1 cup green olives

1 pound of sliced tomatoes

1/2 cup olive oil

2 tbs. capers

1/3 cup vinegar

3 stalks celery, diced

1 tbs. sugar

Slice and dice eggplant in 1/2 inch squares. Slice and sauté onions in 1/4 cup olive oil. When they are golden, add tomatoes. Then add rinsed capers, celery and pitted olives, continue cooking until tomatoes are done, remove pan from heat. Sauté eggplant in remaining 1/4 cup of oil, add to vegetable mixture. Mix vinegar and sugar and pour over mixture, toss. Serve hot or cold.

Caponata, a family favorite, was always served at Gertrude’s dinner table, a nice addition to the main meal as an appetier or a side dish. Or, as is done in Italy, caponata can be served as primi piatti, a first course, along with such dishes as olive condite. Our family would usually serve caponata cold.

Gertrude always was a stickler for good education, and made sure the same fate of not being able to finish school didn’t befall her own children. She would insist that no matter where the family moved, it must be an area with an excellent school system.

Gertrude always was a stickler for good education, and made sure the same fate of not being able to finish school didn’t befall her own children. She would insist that no matter where the family moved, it must be an area with an excellent school system.

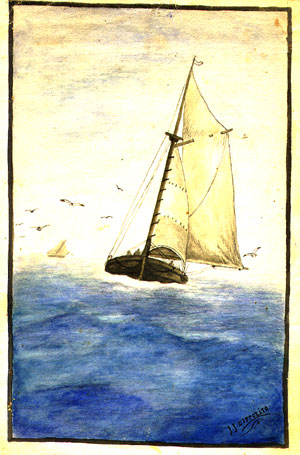

John Angelo Periale & Gertrude D'Ippolito marriage certificate

Gertrude did go back to Old St. Patrick’s to be married. Her favorite nun and teacher, Sister Josita, attended her wedding.

Gertrude did go back to Old St. Patrick’s to be married. Her favorite nun and teacher, Sister Josita, attended her wedding.

Paula Periale, c. 1934

Once, when Paula brought a girl friend home to Sunday dinner, the little girl was amazed when she saw the elaborately-set dinner table.

“Are you having a party?” she asked Paula.

Paula, surprised, responded, “No, this is how we set the table.” It was laid out with silver and dish after dish of family delicacies. At a young age Paula and her brothers realized that the rest of her friends didn’t live this way—and certainly didn’t eat this way!

Once, when Paula brought a girl friend home to Sunday dinner, the little girl was amazed when she saw the elaborately-set dinner table.

“Are you having a party?” she asked Paula.

Paula, surprised, responded, “No, this is how we set the table.” It was laid out with silver and dish after dish of family delicacies. At a young age Paula and her brothers realized that the rest of her friends didn’t live this way—and certainly didn’t eat this way!

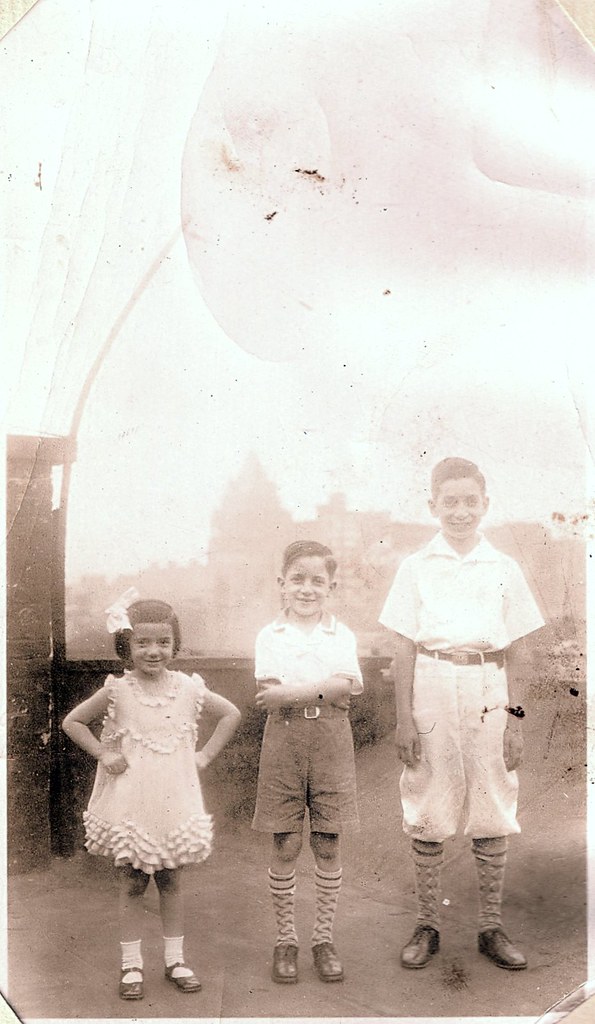

L-R: Joe D'Ippolito, Paula Periale, Gertrude D'Ippolito, James Gabriel Periale, Joseph Francis Periale, c. 1936 (at May Mahler's house, Bronx, N.Y.)

Don Peppino died at the onset of the Depression, in 1933, and the family fortunes went downhill. The family had to leave 14th Street, moving to the Bronx, living in very close quarters and reduced financial circumstances. John Angelo answered an ad in the paper, soon after Pearl Harbor, for a job developing radar. He commuted from the Bronx to Belmar, New Jersey, where the job was based, at Camp Evans, Fort Monmouth. By February 1942, he moved the family permanently to the Jersey Shore.

During those days Joseph built a short wave radio with his father—they got signals from all over during the war. John Angelo also invented the “periometer” a precursor of the odometer, complete with maps for planning various trip routes. John Angelo would also give “treatments" (chiropractic) much like his father-in-law, Don Peppino. But with John Angelo, patients wouldn’t come to the house, he would go to them.

John Angelo Periale, c. 1918.

John Angelo was quite a Renaissance man. As my brother John James puts it,

John Angelo was quite a Renaissance man. As my brother John James puts it,

“In my father (Joseph)’s opinion, John Angelo was the greatest scientist, inventor, doctor, magician, lawyer, herbalist and especially, supplier of homemade birth-control suppositories that ever lived.”After they moved to N.J., John Angelo made Joseph’s day by telling him that the Yankees would be training at Asbury Park High School. Joseph was a senior in high school at the time and stayed after school every day while they were training to watch his favorite team.

Evwn though Gertrude and the family had moved to New Jersey, Giovannina didn’t want to leave the city at first, after her husband’s death, so she stayed in the Bronx, living with Battaglia cousins. She then got a bad case of flu and was admitted to Bellevue Hospital. A close family friend, Pete DiPeri (husband of Gertrude’s greatest friend, May Mahler), who ran a funeral parlor in New York, contacted the family and told them not to worry, he would bring her home from the hospital to live with them in New Jersey. Giovanna was “delivered” to her family from the hospital:

When Pete picked her up he and his assistant were sitting up front in his company vehicle, a hearse. Would she mind riding in the back? Giovanna, a good sport, agreed, grateful for the lift and to be getting home to her family. She laughed on the ride from New York, all the way down to Belmar, as the two men regaled her with jokes and stories. According to Paula, Gertrude’s next-door neighbor almost had "an apoplexy" watching them unload a hearse!

L-R: Johanna D'Ippolito and Paula Periale, July 8, 1934

Aunt Paula, called Pauline as a child, shared a bed with her maternal grandmother, Giovanna throughout her childhood. When Johanna D’Ippolito, her cousin, wanted to take piano lessons, the family came up with a scheme. John Angelo and Gertrude couldn’t afford to give Paula weekly lessons, so they arranged for her to have them every other week with Johanna. Paula’s family had the piano, Johanna’s family had money for lessons . . . they worked something out. Johanna would take her weekly lesson in the Periale apartment and Paula could observe and learn. But the teacher wasn’t thrilled with this arrangement and always treated Paula like a second-class citizen. Giovanna would always sit and listen to the lesson. Giovanna was musical and played the piano. She also liked to play operas on the Victrola and sing along to them, much like her daughter did many years later, singing along to the Metropolitan Opera on the radio on Saturdays, to the enjoyment of her listening family.

Aunt Paula, called Pauline as a child, shared a bed with her maternal grandmother, Giovanna throughout her childhood. When Johanna D’Ippolito, her cousin, wanted to take piano lessons, the family came up with a scheme. John Angelo and Gertrude couldn’t afford to give Paula weekly lessons, so they arranged for her to have them every other week with Johanna. Paula’s family had the piano, Johanna’s family had money for lessons . . . they worked something out. Johanna would take her weekly lesson in the Periale apartment and Paula could observe and learn. But the teacher wasn’t thrilled with this arrangement and always treated Paula like a second-class citizen. Giovanna would always sit and listen to the lesson. Giovanna was musical and played the piano. She also liked to play operas on the Victrola and sing along to them, much like her daughter did many years later, singing along to the Metropolitan Opera on the radio on Saturdays, to the enjoyment of her listening family.

James Gabriel Periale, July 8, 1934

Paula’s point of view, of her youngest brother James Gabriel (Jim)’s birth: The day Jim was born she was in summer camp across the street. It was the last day of camp and the children were putting on a pageant. A beautiful costume of “Little Jack Horner” had been made for her by her cousins, Palma and Dorothy Battaglia. Joseph and John were also in summer camp and in the play. A bunch of toughs came up to her after the performance and pushed her around, pulling her costume apart. The five-year-old Paula was distraught and ran home. Palma saw how upset she was and said, “Don’t worry, we have a great surprise for you!” and took the little girl upstairs. There she saw her mother Gertrude in bed with the newborn baby Jim.

“This is my surprise?” Paula said, disappointed, still upset about her costume.

Paula’s point of view, of her youngest brother James Gabriel (Jim)’s birth: The day Jim was born she was in summer camp across the street. It was the last day of camp and the children were putting on a pageant. A beautiful costume of “Little Jack Horner” had been made for her by her cousins, Palma and Dorothy Battaglia. Joseph and John were also in summer camp and in the play. A bunch of toughs came up to her after the performance and pushed her around, pulling her costume apart. The five-year-old Paula was distraught and ran home. Palma saw how upset she was and said, “Don’t worry, we have a great surprise for you!” and took the little girl upstairs. There she saw her mother Gertrude in bed with the newborn baby Jim.

“This is my surprise?” Paula said, disappointed, still upset about her costume.

The Periales

For the most part, when it came to cooking, Gertrude stayed with what she knew. My grandfather John Angelo Periale’s family had come from Northern Italy, Torino, and he occasionally persuaded Gertrude to make a few Northern dishes—every once in a while John Angelo would insist on having one of his favorite childhood dishes, especially polenta.

Polenta is cornmeal mush, a northern Italian pasta-substitute. The best time to make polenta would be after Gertrude had cooked a roast. John Angelo would chop what meat was left over from the roast into small 1/4 inch cubes, trimming off all the fat, and make gravy. Then Gertrude would make the polenta:

PolentaThe polenta can be left to set and then cut into squares. The way John Angelo liked to serve it was to pour the gravy over the whole platter. He would then encourage everyone to reach over the center of the table to the platter and spoon a great big serving onto their plates. They only served his favorite dish once this way, the “correct” way, because Gertrude didn’t like serving it in the "peasant" manner. She had come a long way to get away from that kind of life. John Angelo thought of it all as fun. It was communal and reminded him of his childhood. He was a playful person and offset Gertrude’s serious, and sometimes rigid, side.

In a medium size pot mix 2 cups cornmeal with 3 cups cold water Add this mixture to 3 cups boiling water Stir with a cucciata (wooden spoon). Spread polenta out on a big platter or, more traditionally, a large wooden board.

When Gertrude was once again persuaded to make polenta for John Angelo, she would place a spoonful of the cornmeal neatly in bowls and ladle a dollop of gravy on top, serving it with a vegetable on the side.

Another aspect of the polenta-making process that didn’t thrill Gertrude was the mess it made out of her pots, as it adhered to whatever pot or pan she was using like glue.

I have made polenta with sausage:

Saute onions, garlic, mushrooms, green peppers in a pan with olive oil. Add some sweet Italian sausage, cook together until sausage is done. Pour over polenta.Frankly, I’m with Grandma on this one. It takes forever to scrape the remains of the mush out of the pots. I prefer the above mixture ladled over pasta.

As to other northern Italian specialties, on special occasions, usually Christmas, the family also had pannetone and sometimes John Angelo would prepare risotto with chicken livers. John Angelo would usually cook any of his Northern Italian family dishes and Gertrude would make eggplant parmigiana and other Sicilian delicacies she learned from her father, Don Peppino.

Cooking helped my grandparents keep their family traditions alive and pass them along to the younger generations. They may have been called "Italians" by their neighbors, but as far as their Italian identity was concerned, John Angelo spoke Piedmontese and Gertrude Siciliana. They spoke English to each other; they couldn’t really converse in their Italian dialects. They truly were an American couple.

Massimo

Massimo, John Angelo's father, married Paola Cerchio and had four daughters: Della, Lena, Rose and Ernie, left on a boat for America from Rotterdam. He found himself on the boat with a lot of Germans and by the time he landed in America he had become very friendly with a family and their daughter, a young woman the Periale family refers to as the “Pennsylvania Dutch girl.” So far I haven't found the ship's manifest Massimo's first trip to America.

Back in Italy, the family was wondering what had become of Massimo. He was ostensibly working hard to raise money to bring he rest of the family to join him in America. They finally sent Parin (godfather), Paola’s father, to America to find out what had happened to Massimo. Upon arrival Parin soon tracked down his wayward son-in-law. Massimo quickly had to say good-bye to the Pennsylvania Dutch Girl. Parin brought Massimo back home to Italy. Massimo brought family (minus Della) back to the United States in 1891: his wife Paola (26) and daughters Carolina (6), Rose (4) and Ernie (2). Daughter Adela (Della) was just an infant, one year old and was left with friends.

The story that has come down through the years is that the family didn’t have enough money to send everyone overseas, so it was decided that Della, the youngest, would be shipped off to stay with another family and left in Italy! There are a different versions of this story:

1. She worked for this other family as a governess (Not correct at all, as evidence shows she was a baby when they went to America.)

2. The Periales had a food business (a bakery), and when you have a food business you can’t nurse a child, so they gave Della over to another family to raise and they paid for her keep. This (Gertrude’s) interpretation puts Della at a much younger and actually correct age, as I was able to find the ship's passenger list (below) that shows the family came over when she was just a one-year-old. How was Paola able to leave such a young child? I can't even imagine leaving my baby daughter with anyone, in another country, whether they were family, friends or otherwise. Della was eventually sent for, but many years later. I am still looking for the record of that trip. Della shows up on the 1900 U.S. Census, age ten. So she must have been sent for between age one and ten . . .

Massimo and Paola had three more children, all born in America: Frank (b. 1892), Margaret (b. 1898) and John Angelo (b. 1896), my grandfather.

There is a pile of stones near Susa, a small town outside of Torino, in the north of Italy near the French border, where the Periales are said to come from. There is a castle of the Marchesa Adelaide, who once ruled in those parts. John Angelo’s sister Adelaide (Della) was named after the Marchesa.

John Massimo took Rose once to the border between France and Italy to Susa to see the “rockpile.” Locals told them that Periale means “for the King, pro-Royal. James Gabriel also visited Susa and learned that the name also appears right over the border in France, where it is spelled Perreal or Perial. He once met a genealogist who told him about the French spelling of our surname. The genealogist also showed him an elaborate map illustrating the locations of many Perreals along the French border with Italy. To James Gabriel’s surprise, on the other side of the border, in Italy, there were just as many Periales. The genealogist explained that the two names meant the same thing, "loyalty to the king" and that the Perreals/Periales were originally a border outpost guards.

Whether Della got her name from the Marchesa or not, she was definitely family royalty. She was a true American success story, becoming an entrepreneur in the pharmaceutical industry with her husband, Daoud (David) Himadi, but upsetting the family by marrying a non-Italian.

As an adult, Della became a success on her own, marrying David Himadi and living in a style higher than the rest of the family. One story John Massimo told, which he must have heard from his father, John Angelo:

Della and Hamadi visited the Periales at their farm in New Jersey (c.1909-10) once with a brand new Cadillac. Whenever these two family factions would come together, sparks would be likely to fly. After the family dutifully admired the beautiful car, David Himadi put the new car in the barn so no dust would get on it and no one would bother it. They all moved inside to visit and soon sat down to dinner. John Angelo, the youngest (at 14), fidgeted restlessly at the dinner table. He could think of nothing but that brand new Cadillac since it had arrived. And how it was sitting unattended in the barn. He was finally allowed to excuse himself from the table. He headed quietly and swiftly out to the barn.

After dessert David and Della said their goodbyes and walked out to the barn to retrieve their car. David opened the barn door to discover the Cadillac—in pieces—all over the barn floor. John Angelo, fascinated to see how things worked, had taken it apart! David looked as if he wanted to kill him.

Massimo, John Angelo’s father, stepped between them. “Now wait a minute,” Massimo said and turned to his son, “Now take those shafts down off the wall, put the wheels back onto the Cadillac. Put a horse in front of it and ride it down to the blacksmith’s and watch him put it back together. You’ll know what to do next time!”More from John Massimo: John Angelo never liked David Himadi. They never got along. He reportedly cried in anger at Della’s wedding. Della eventually didn’t get along with her husband, either. They didn’t spend more than eight months together after their second son George was born.

When the Periale family went to visit Della at her house, everyone would make gnocchi together:

Gnocchi (with cheese)from Italian Regional Cookery: A Culinary Travelogue by Bea Lazzaro

1 pound ricotta cheese

2 cups of flour

1 egg

1/4 cup butter

1 teaspoon salt

1/2 cup grated Pecorino and Parmesan cheese

Mix all the ingredients together in a bowl with your hands until it holds together as a dough. Cover and let rest for 5 minutes. Turn out on a floured board and knead until smooth. Roll into 3/4 inch ropes, cut into 1/2 inch pieces. Cook in boiling salted water for about 5 minutes. Drain and serve with your favorite sauce!

Massimo, John Angelo’s and Della’s father, is a family legend. At the age of eleven his family in Piedmont, in Torino, wanted to make him a priest. Massimo did not want to be a priest. He took off and crossed the border to Switzerland. He soon became hungry, and walked into a bakery. The couple who owned it were childless. They took him in and trained him as a baker. He eventually returned to Torino (Turin), opened a bakery, and met and married Paola Cerchio.

This story sounds similar to another family tale about a male Periale (brother or cousin of Massimo?), the son of a professor in Torino, who was studying for the priesthood. The night before he was to take his orders her eloped with the gardener’s daughter.

Paola Cerchio was also from Torino. Her father Parin’s brother, called Barbarossa (Red Beard), “Daddy’s Mother’s Uncle,” a political radical, escaped to England, and fought for that country in the Crimean War. Barbarossa not only had an imposing name, but also an imposing frame: he was such a large man that he would fill the doorway as he entered any room.

In Savoy, Barbarossa almost killed another military officer who was taunting him. He threw him down a ladder which went up to one of the parapets of the fort where they were stationed. He was sentenced to 50 lashes (the death sentence in those days).

The family, having some influence, got him off with only 10 lashes.

Barbarossa was brought back to his cell, where he wrote an eloquent letter to La Duchessa of the region of Savoy. Torino was located in the province of Savoy. La Duchessa was so touched by Barbarossa’s poetic letter that she granted his release. He later went to England and fought in the Crimean War (probably c. 1855 when Piedmont entered the war.). Years later he met and married a woman named Margaret. John Angelo’s sister Margaret was named after her. There is also mention, on the Periale side of the family of a Barba Felipe—another family nickname?Barba Felipe (Uncle Philip) may have been Massimo’s brother. James Gabriel's description of him closely resembles Barbarossa: Massimo and Philip took different ships and Philip was never heard from again. The family believed he went to a Argentina. The most notable thing about Phillip was his size (very large) and his red hair. There were many stories about his adventures in Italy and to his nieces and nephews and grandchildren "Barba Felipe" was a true hero.

One of Massimo’s brothers paved the way for the Periale family to come to America. This brother fell in love with a local rich girl. The two young lovers planned to elope, but her brothers came after them to prevent the marriage. There was a fight, and Massimo’s brother killed one of the girl’s brothers. Massimo must have been involved somehow, because both he and his brother had to flee Italy. They left Europe through the Netherlands. The brothers were said to have left on two different boats, Massimo to the United States and the brother to South America. Lena’s husband John Giardino tried very hard to find Massimo’s brother, but never had any success.

When John Angelo was just a baby, his older sister Ernie was told to take him out for a walk. She set him in the pram and pushed him to the top of the hill near where they lived in Paterson, New Jersey. Walking her baby brother’s carriage at first seemed a chore, but Ernie, who was always on the lookout for a game, soon got an idea of how to make it more fun. She turned the carriage around and pushed it back to the top of the hill. She gave the pram a little push and hopped in behind John Angelo as it started to roll down the hill. For a few moments it was a fun, like a rollercoaster ride, but when they got to the bottom of the hill the pram hit a rock and went over. Ernie went out one side of the carriage and the baby went out the other, flying into a horse trough! Luckily neither was harmed, but John Angelo was sopping wet. Ernie walked him around for hours, waiting for him to dry off. When she finally brought him home, Paola asked her where they had been all afternon. ”Out for a walk,” she said proudly. Paola took this answer in quietly and responded, “Ernie, then could you answer one question - why are the baby’s clothes on backwards?”

One day as Ernie and her girlfriends were walking to the store, Ernie’s older sister Rose gave her some money and asked her to bring her back some licorice candy. She gave her enough money to buy some candy for herself, as well. On the way back from the store, Ernie, chattering with her friends and paying no attention, ate all of her licorice candy and most of her sister’s. She got an idea of how to make the bag look more full.

She substituted rabbit turds!

On another occasion Ernie’s father Massimo wanted her to go with him to deliver bread. Ernie didn’t want to deliver bread, she wanted to go and play with her friends. But she wasn’t going to tell him that. Instead she said, “No, today I’m going to go to church.”

“You never go to church, what do you mean you’re going to church?,” asked Massimo.

”Well, today I feel like going to church.” So Massimo got on his wagon and headed off down the road. She took off in the other direction.

Massimo’s no dope: he turned the wagon around and came back up the street. He found her as he turned the corner, playing with some kids from down the road. She looked up and saw him, staring at her, fuming. She figured, “I better go to church!”

She took off from her game, ran up the road and into the church. Massimo jumped off the wagon and ran after her, brandishing the horsewhip.

It was a hot summer day, and Massimo only had on an undershirt and his pants and a cap. The church ushers promptly threw him out. Ernie stayed for the 7:00 mass, the 8:00 mass, the 9:00 mass, the 10:00 mass, the 11:00 and 12:00. The old man waited outside the church doors until she finally came out in the late afternoon and still gave her a hiding.

The family moved to Lodi, New Jersey and Massimo opened a bakery. The Periale

Bakery was not a storefront, however, it was a bread delivery service. Massimo would go out with the horse and wagon on Saturday morning to deliver bread and to collect accounts from the stores and homes that were his clients. Quite often by 6 pm he hadn’t returned home. Paola would become worried and ask John Angelo to go out and see if he could find his father.. Ten minutes after he left the house John Angelo would see the horse coming up the road, leading a seemingly empty wagon. Massimo would be laid out in the back, drunk. They would bring him into the barn. Sometimes he would get up and come into the house. Sometimes they would leave him there and he would sleep it off. No matter how often this happened, with Massimo being late, Paola would always get worried and ask John Angelo to get on a horse and go out and look for his father.

Massimo was laid up with a cold one February, so Paola had to take care of any customers who might call. One day a Mrs. Martini came by to pay something on her bill. Paola knew that Massimo kept an account book with all the customer’s names in it. She found a black bound book behind the counter and opened it to look up her account. She began turning pages, turning redder and redder with each page’s turning. She finally closed the book and told Signora Martini that she’d better come back another time when her husband was feeling better. She then went upstairs, the book under her arm and marched into their bedroom where Massimo lay fast asleep and hit him hard over the head with it.Paola was very quiet and sweet natured and Massimo loved to tease her. One cold morning they were looking out of the window at the chickens scratching in the dirt and Paola, a timid soul, was afraid that the chickens would freeze during the cold winter months. “How will we keep the chickens warm?” asked a worried Paola. Massimo answered, “You know what you should do, you should knit them booties.” She took him at his word. “Oh, naturalmente!” And she did!

Massimo woke up, shouting, “What’s the matter with you?”

She answered, “What’s this?” and tossed the book at his head. He saw what it was, and started laughing. Massimo’s method of keeping accounts was: Signora Martini, la putana con la culla grande (the whore with the fat ass).

There were other descriptive phrases such as “ugly face” and “the slob.” That’s how he (privately) got even with his difficult customers!

Paola’s father Parin owned a tavern nearby. One of the services provided by the tavern was a stagecoach line. The stagecoach picked up people and took them to the train line that ran to the ferry that ran to New York City. A lot of local businessmen frequented the tavern. One of them was David Himadi. According to John Massimo, that is how he and Della met.

When John Angelo was just a kid his father decided that the family cat was becoming a nuisance. One day his father Massimo said, “Listen, you - when you come home from school, tomorrow, I want you to put some rocks in a flour sack and put that cat inside it and throw it into the Passaic River.”

John Angelo was horrified at the idea, but he was more terrified of his father. So when he got home he dutifully put the cat in a flour sack and carried it down to the river, blubbering all the way, but also trying to steel himself for the job. He reached the river, twirled the sack above his head and threw the bag in, with a sickening splash. On the long walk home he cursed both his father and the cat. When he came in the door, Paola saw him with a wild expression on his face and exclaimed, “Where have you been?” But John Angelo was staring above and beyond his mother’s face, his mouth hanging open in shock, because at the top of the stairs on the landing was the cat, soaking wet, calmly grooming itself.

He was never able to stand being around a cat after that.

Elizabeth Anne Periale & Gertrude D'Ippolito, c. 1967, Wall Township, N.J. house, 2175 8th Avenue, Twinkle (?) in background

His son Joseph, on the other hand, loved cats. We always had cats around the household when I was a child. John Massimo presented us with a “guaranteed male” stray once on a visit, who proceeded to have about five litters in close succession. My father had named “him” Twinkle. Joseph felt that this was yet another example of his older brother one-upping him. Joseph was always great at naming cats: Puddin’, Cricket, Cotton & Pepper (sisters), Pudge and Tootsie were all illustrious felines and lived up to their monikers.

Paola died c.1926

After Paola died, the family wondered what they were going to do with Massimo. He didn’t want to go to live with anyone in the family, he wanted to live on his own. He bought a farm in South Jersey, near Fort Dix with 3 acres of arable land, 23 acres of woods. He decided he was going to raise chickens and got about 2,000. He was in his seventies at the time.

One day one of his old paisanos from northern Italy came by to visit and said to him, “You know, Celin, with all this land and those woods near the fort, you could make some nice money making some whisky.”

It didn’t take long for Massimo to decide, “Let’s go!”

So the two old pals started making booze. This was taking place during Prohibition, of course.

John Angelo, who at this time was living with his family in the Bronx, drove down to New Jersey one day to check on his father and see how he was doing. They spent the day together. John Angelo came back to New York and told Gertrude, “You know, something’s going on down there. I can’t quite put my finger on it. But there are chickens all over the place. In the house. In the yard. He’s got a big wine press. It’s a mess, there’s no order anywhere. And there’s this awful smell coming from the woods.”

About a month or so after his visit John Angelo got a call from one of Massimo’s neighbors, a farmer who lived down the road, “Mr. Periale—you better come down here right away, your dad’s in trouble.”

John Angelo got into his Flint and drove down to New Jersey. He looked all over the farm, but there was no sign of Massimo. He made some calls and finally got hold of the family’s resident problem-solver, Della. She told him, “Yes he’s here and we’ve got problems. You better come up.”

So John Angelo got back in his car and headed up to Ridgewood in North Jersey. Della had quite a story to tell.

The last time John Massimo saw his grandfather was two months before Massimo died. John Angelo took him to see his grandfather, who was ill in bed. John Angelo told his father that John Massimo was going to enlist in the army. The old man said, “Stai Forbo!” (Be bold!)

“What are you going to do?” “I’ll advertise in Catholic Digest and sell each grain of sand as a grain from the bones of St. Cecilia!” He was only kidding, thankfully.

On the same trip they rented a car in Rome and drove down to Naples, hoping to visit the ruins of Herculaneum and Pompeii. Unfortunately the sites were closed on Mondays. As it was approaching lunchtime, John Massimo suggested they find a little restaurant and have a nice lunch. They liked the wine that was served with lunch so much that they decided to get four bottles to take with them. The restaurant proprietor wrapped the bottles in napkins and put them on the back seat of their car.

His son Joseph, on the other hand, loved cats. We always had cats around the household when I was a child. John Massimo presented us with a “guaranteed male” stray once on a visit, who proceeded to have about five litters in close succession. My father had named “him” Twinkle. Joseph felt that this was yet another example of his older brother one-upping him. Joseph was always great at naming cats: Puddin’, Cricket, Cotton & Pepper (sisters), Pudge and Tootsie were all illustrious felines and lived up to their monikers.

Paola died c.1926

Paula: Dropsy? Parkinson’s disease?

John Massimo: Whatever she had, she died!

After Paola died, the family wondered what they were going to do with Massimo. He didn’t want to go to live with anyone in the family, he wanted to live on his own. He bought a farm in South Jersey, near Fort Dix with 3 acres of arable land, 23 acres of woods. He decided he was going to raise chickens and got about 2,000. He was in his seventies at the time.

One day one of his old paisanos from northern Italy came by to visit and said to him, “You know, Celin, with all this land and those woods near the fort, you could make some nice money making some whisky.”

It didn’t take long for Massimo to decide, “Let’s go!”

So the two old pals started making booze. This was taking place during Prohibition, of course.

John Angelo, who at this time was living with his family in the Bronx, drove down to New Jersey one day to check on his father and see how he was doing. They spent the day together. John Angelo came back to New York and told Gertrude, “You know, something’s going on down there. I can’t quite put my finger on it. But there are chickens all over the place. In the house. In the yard. He’s got a big wine press. It’s a mess, there’s no order anywhere. And there’s this awful smell coming from the woods.”

About a month or so after his visit John Angelo got a call from one of Massimo’s neighbors, a farmer who lived down the road, “Mr. Periale—you better come down here right away, your dad’s in trouble.”

John Angelo got into his Flint and drove down to New Jersey. He looked all over the farm, but there was no sign of Massimo. He made some calls and finally got hold of the family’s resident problem-solver, Della. She told him, “Yes he’s here and we’ve got problems. You better come up.”

So John Angelo got back in his car and headed up to Ridgewood in North Jersey. Della had quite a story to tell.

That morning Massimo was at the farm as his buddy came chugging down the road in his car and said, “Get in, they’re 15 minutes behind me.”

He was referring to the revenue agents. They chased the two old geezers all the way from South Jersey up to Ridgewood. With David Himadi’s pull, he and Della kept Massimo out of jail by pleading compassion; appealing to the judge with Massimo’s age and his recent loss of his wife.

The judge called him up to the bench and started to give him a lecture. Massimo, interrupting, turned to Della, “What’s he talking about?” Della whispered, “You’re not supposed to make whisky.” Massimo, angry said, “Nobody tells me not to make whisky. If I wanna make whisky, I make whisky!” Della, in a louder tone, “ Shut up! Take your hat off!” Massimo, stubbornly, “But I make whisky!” Della, even louder, “Shut up!”He almost got thrown in jail. John Angelo, who had studied law, helped negotiate. Della paid the fine. The still was confiscated. The agents discovered a big hole in the fence between Massimo's property and Fort Dix. He had been selling bootleg whiskey through the fence to the GI’s!

The last time John Massimo saw his grandfather was two months before Massimo died. John Angelo took him to see his grandfather, who was ill in bed. John Angelo told his father that John Massimo was going to enlist in the army. The old man said, “Stai Forbo!” (Be bold!)

When he was 15 or so, Uncle John Massimo won a city-wide public speaking contest. He won $50.00 and a trip to Italy. Two Italian police were sent to America to look for Italian-origin students who excelled in some area. At the awards ceremony the master of ceremonies announced that John had not only won the contest, but that he had been selected to go on a trip to Italy with 150 other boys. Two priests were there from the Italian Consulate to award the prize, which was at the cost of the Italian Government. They sailed on the S.S. Roma to Europe. John had just graduated grammar school. The entire family was excited.

Unbeknownst to anyone, it was a fascist propaganda trip. They sailed to Marseille, Spain, Haifa, Genoa. On landing in Genoa they were put into uniforms—blue shirts—and were told this would help their guides to keep better track of them.

Photographers took pictures of all the American children in Italian uniforms. They continued on a fabulous trip through Italy. They were taken to Milan where they visited the Duomo and La Galleria; Florence and Rome. They would have gone to Venice, but the war was in full force. In Rome they had an audience with Mussolini.

Then they were brought to the Vatican where they were given an audience with Pope Pius the 12th. John Massimo even kissed his ring. The sightseeing continued with a special tour of the catacombs. Then they were taken south to Naples, where they were housed at the Italian military school, headed by crown prince Umberto. John Massimo thought he was a great guy, a “crackerjack.” They went on an excursion from there to Pompeii. The trip lasted the whole summer.

When he finally came home, Gertrude and John Angelo gave a party for John to regale all the relatives with stories from his amazing trip. Everyone came over to hear his adventures while his proud parents looked on. But as he talked on, telling various anecdotes his father started to become uneasy. And when he topped off the evening by singing “ Il Giovanettzo,” a fascist youth song, his father’s jaw dropped. After everyone headed for home he took John aside and tried to explain to him that the Italians had tried to turn his head with fascist propaganda and that he should be proud he was an American.

It took John Angelo weeks to straighten him out, as John Massimo continued to spout all the propaganda which had been fed to the children throughout the trip. All John Massimo remembers now of that song, “Giovinezza,” is its title.Years later John Massimo took Rose to the Roman Catacombs under the Church of St. Cecilia. He reached into a hole and pulled out a handful of dust. “I’m going to make money.”

“What are you going to do?” “I’ll advertise in Catholic Digest and sell each grain of sand as a grain from the bones of St. Cecilia!” He was only kidding, thankfully.

On the same trip they rented a car in Rome and drove down to Naples, hoping to visit the ruins of Herculaneum and Pompeii. Unfortunately the sites were closed on Mondays. As it was approaching lunchtime, John Massimo suggested they find a little restaurant and have a nice lunch. They liked the wine that was served with lunch so much that they decided to get four bottles to take with them. The restaurant proprietor wrapped the bottles in napkins and put them on the back seat of their car.

As they headed back to Rome with Mt. Vesuvius on their left, John Massimo remarked, “Boy, the wind must really be blowing this way, Can you smell that sulfur?”

Rose turned around and looked at the back seat, “That sulfur you’re smelling is all over the floor of the car.” One of the bottles had popped and spilt all over the back seat. It cost fifty dollars to get the rental car cleaned.

Joseph liked to tell a story about his older brother:

Rose turned around and looked at the back seat, “That sulfur you’re smelling is all over the floor of the car.” One of the bottles had popped and spilt all over the back seat. It cost fifty dollars to get the rental car cleaned.

Joseph liked to tell a story about his older brother:

When Joseph was just 5 years old his brother John (4 years older) was assigned the duty of picking him up and walking him home after school. It’s amazing that my father ever got home, because John was always off playing stickball or some such game with his pals and would forget about Joseph.

Paula, Joseph Francis & John Massimo Periale, c. 1931

But little Joseph sat on the school steps, faithfully awaiting his brother’s arrival (because that is what he was told to do.) Back on 14th Street, it got darker and darker and still no Joseph at home. Gertrude was frantic. When John finally rolled in the door solo around 8 p.m., all hell broke loose. Needless to say Joseph was retrieved and John was probably walloped. My dad did enjoy telling that one!

L-R: John Massimo Periale, John Angelo Periale, Joseph Francis Periale, Paula Periale, James Gabriel Periale

The brothers definitely bonded on a later occasion:

The brothers definitely bonded on a later occasion:

The D’Ippolito-Periale household was a large one and they all lived in one railroad apartment in the Bronx. John and Joseph shared a bedroom. During summer it was quite hot and the boys slept with the windows open, as did the rest of the city dwellers. One night Joseph was awakened by his brother, “Hey, Joe, c’mere!” When he joined his brother at the window they got quite a show from the couple across the alley. The rest of the week their mother would be amazed as John would announce that he was going to bed, earlier and earlier each night, with his little brother in tow. One night Gertrude came in the room and discovered the true reason, as she discovered the boys propped up against the window ledge, watching the neighbors. Gertrude and John Angelo immediately switched rooms with the boys. John Massimo is still convinced his parents reaped the benefits of that hot summer.John James's impression of John Massimo:

The colonel, the general, every story was important, every joke was funny, dammit! In my uncle’s presence my father would be forever ten years old.When Joseph was a kid in the Bronx he had a blast, running around with a gang of kids, playing games like stickball, shooting marbles, flipping baseball cards.

furnace/cuckoo clock/string

Dear Elizabeth Periale,

ReplyDeleteI'm so glad that I found this information, thank you for posting this. If you're wondering who I am; I'm Millie D'Ippolito, Daughter of Joseph D'Ippolito. You can contact me at milagrosve1@hotmail.com, I'm looking forward to your e-mail.

Elizabeth

ReplyDeleteI just found your blog and was enthralled by your family story. My father Raymond (who is 94) is the son of Fanny D'Ippolito and Francesco (Frank) Battaglia. I have been working on my family tree and will add this info to it.

Thanks

Anne Battaglia Marques